Latest in the Labs: The Ancient Agriculture and Paleoethnobotany Laboratory

There is a close relationship between people and plants, and they influence each other, explains  Reuven Sinensky, a paleoethnobotany graduate student in the Department of Anthropology. For the past six years at UCLA, he has been studying these influences with the support of the Ancient Agriculture and Paleoethnobotany Laboratory, a collaborative research space within the Cotsen Institute dedicated to the investigation of agricultural systems and communities in the past, as well as the analysis of archaeological plant remains.

Reuven Sinensky, a paleoethnobotany graduate student in the Department of Anthropology. For the past six years at UCLA, he has been studying these influences with the support of the Ancient Agriculture and Paleoethnobotany Laboratory, a collaborative research space within the Cotsen Institute dedicated to the investigation of agricultural systems and communities in the past, as well as the analysis of archaeological plant remains.

“Throughout human history, from our earliest ancestors through to modern societies, plants were of vital significance,” according to postdoctoral fellow Sonia Zarrillo, who has been the director of the Ancient Agriculture and Paleoethnobotany Laboratory for the past two years. She describes herself as an anthropological archaeologist with a specialization in paleoethnobotany. “Plants have been essential to diet, used as medicines and in ceremonies, fashioned into a myriad of tools, containers, adornments, and musical instruments, depicted in artwork, used as emblems, and relied on as a source of fuel and building materials,” she continued.

significance,” according to postdoctoral fellow Sonia Zarrillo, who has been the director of the Ancient Agriculture and Paleoethnobotany Laboratory for the past two years. She describes herself as an anthropological archaeologist with a specialization in paleoethnobotany. “Plants have been essential to diet, used as medicines and in ceremonies, fashioned into a myriad of tools, containers, adornments, and musical instruments, depicted in artwork, used as emblems, and relied on as a source of fuel and building materials,” she continued.

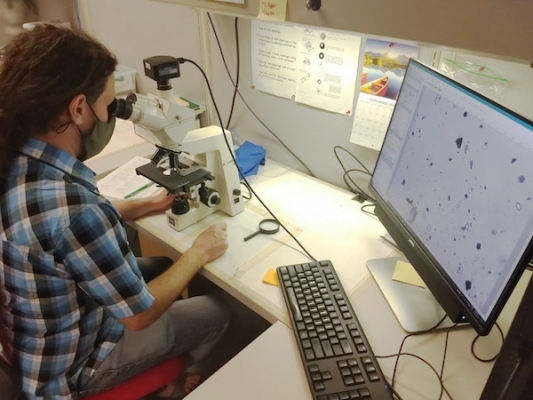

Students use all methods available in the laboratory to investigate ancient agriculture or human-plant interactions, including both macro- and microbotanical analyses. It is the microbotanical examination, possible only with specialized equipment brought in by Zarrillo, that has been critical to the recent work on ancient starch that Sinensky has been doing with Zarrillo on artifacts from a number of sites in Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona. They are looking at the starch that has been preserved on grinding tools, so that they can determine what was being intentionally ground. Very few studies have used starch grain analysis in the American Southwest.

“It is a huge addition to what we can learn about what people were doing in the past, how they were doing it, and when they were doing it,” Sinensky explained. “We are also taking starch samples from pottery, so we are hoping that we can identify what people were cooking or doing in those earliest pots in the region. This can help us understand when and why people adopted ceramics,” he added. Sinensky has also worked with Alan Farahani, a previous postdoctoral fellow at the Cotsen Institute who directed the laboratory for four years before Zarrillo arrived. He collaborated closely with Farahani and still does. Farahani is currently assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “We worked really well together and talked a lot about theory. How do we do what we do?”

Another student inspired by Zarrillo is Kellie Roddy, an archaeology graduate student at the Cotsen Institute. She is testing for starch on artifacts from the collection of the Fowler Museum at UCLA; artifacts which were excavated by UCLA in the 1960s. She sees this as an additional component to her education, and notes that “doing this kind of research is pretty new. So a lot of this is just creating a baseline of knowledge.” She was inspired by Zarrillo’s specialization in microbotanical analyses: using techniques to recover microscopic plant remains adhering to artifacts, recovering them, and identifying them. One of the aspects that Roddy is dealing with is the possibility of contamination of museum collections. She is doing control samples and hopes to do different kinds of testing on her samples in the future. Zarrillo has now returned to Canada to finish her fellowship remotely, and the equipment and materials that she brought would need to be replaced if Sinensky, Roddy, and other students are to continue this type of research.

There is great interest in paleoethnobotany as evidenced by the 15 students that enrolled in Zarrillo’s class in the winter of 2020. Usually, she noted, graduate classes do not have more than four to seven students. Both Sinensky and Roddy did attend the classes. However, the number of students who can use the Ancient Agriculture and Paleoethnobotany Laboratory is limited by the equipment and the space required to lay out samples. “One of the effects of Covid-19 is that we cannot have more than one person working in the laboratory at a time, due to density requirements. But, regardless of the pandemic, we cannot have more than one person working on a project because we do not have the physical space,” Zarrillo said. At most, the space can accommodate her and a student for training purposes. For example, although both Sinensky and Roddy are working on paleoethnobotanical projects, Roddy is physically using the Experimental and Archaeological Sciences Laboratory across the corridor. Other students would be interested, if only we could accommodate them, according to Zarrillo.

Students in the Ancient Agriculture and Paleoethnobotany Laboratory are encouraged to  build interdisciplinary collaborations with other anthropologists and archaeologists—and subspecialties such as lithic, pottery, zooarchaeological, and human remains analyses—as well as with food scientists, specialists in ancient DNA, and chemists. For example, Zarrillo has worked with Tom Wake, director and senior museum scientist, in the Zooarchaeology Laboratory (the Bone Lab) and points out that a lot more could be done collaboratively between the two. In fact, Sinensky has worked with samples from a “filing cabinet filled with plants” kept in the Bone Lab.

build interdisciplinary collaborations with other anthropologists and archaeologists—and subspecialties such as lithic, pottery, zooarchaeological, and human remains analyses—as well as with food scientists, specialists in ancient DNA, and chemists. For example, Zarrillo has worked with Tom Wake, director and senior museum scientist, in the Zooarchaeology Laboratory (the Bone Lab) and points out that a lot more could be done collaboratively between the two. In fact, Sinensky has worked with samples from a “filing cabinet filled with plants” kept in the Bone Lab.

Paleoethnobotany is an important component in the study of the archaeological record, according to Sinensky. “It helps shed a light on how and when people started living in villages and cities and how they changed the environment around them,” he points out. “We can track through time how people shaped and interacted with the environment. Was it sustainable? Those are questions we can investigate and answer and learn from. We see the fallout from what we are doing now, with everything being on fire. We have got more than 10,000 years of people living in villages and cities, and we can learn from them how to do this right,” he concluded. Work in the Ancient Agriculture and Paleoethnobotany Laboratory is one of the ways to contribute to that body of knowledge.

To support the research in our laboratories, graduate and undergraduate education in archaeology and conservation, or for more information, please contact Michelle Jacobson at mjacobson@ioa.ucla.edu.

Figure 1. A remote interview with Reuven Sinensky, September 20, 2020.

Figure 2. Sonia Zarrillo removes the residues from stone tools found in Petrified Forest National Park (Arizona) treated in an ultrasonic bath. Photo by Sonia Zarrillo.

Figure 3. Reuven Sinensky searches slides of archaeological materials for starch grains with a transmitted light microscope. Photo by Sonia Zarrillo.

Figure 4. Reuven Sinensky works a flotation device in the amphitheater just outside the Cotsen Institute.

Published on October 5, 2020.